Too new to be good

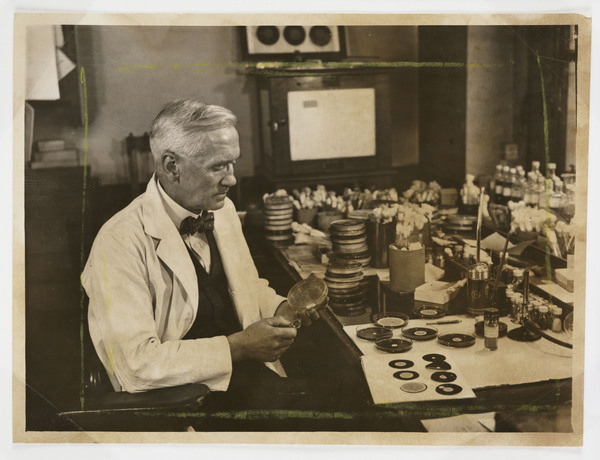

In 1928, the Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming working St Mary’s Hospital in London discovered that the liquid produced by a penicillium mold stopped the growth or even killed certain bacteria. Because he could not extract the agent that was in the liquid, he was unable to make an effective medicine. However, in 1939 Ernst Chain, then at Oxford University, addressed the problem of separation as an interesting chemical challenge. By using the new process of freeze-drying he managed to make a small quantity of impure dry penicillin, which he showed did not have ill effects on mice.

A few months later, colleagues at Oxford showed that mice infected with a fatal bacterium were rescued if they were injected with a solution of the powder, but died otherwise. A large team headed by Howard Florey discovered how to grow the mold, to extract the penicillin more effectively, and to use it as a therapy. The process was very sensitive and the production was very low, even with the assistance of a few British companies. Extraction was done at a laboratory scale. Florey and his colleague Norman Heatley took the Oxford process to the USA, where he found scientists with much more experience of producing useful products from molds at the Peoria laboratory of the Department of Agriculture and at the Pfizer Corporation.

These organizations, which had had pre-war experience in growing air-breathing moulds in deep tanks and links to European centers of excellence in the Netherlands and Prague, developed a new technology for growing the mold which made cheap penicillin possible by 1945.

How to cite this page

Slawomir Lotysz, 'Too new to be good', Inventing Europe, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/story/too-new-to-be-good

Sources

- Grundmann, Ekkehard. Gerhardt Domagk: The First Man to Triumph over Infectious Diseases. Münster: Lit, 2004.