One Europe, many patterns

Sewing machines not only allowed women to produce clothes more quickly, they also helped women from all classes to copy high fashion. In the late 1800s, a new tool invented to aid in this effort was the paper sewing pattern, which allowed women with less formal training to reproduce popular patterns. The American firm Butterick was a pioneer in this regard, as was Burda in Germany.

Sewing patterns printed in women's and lifestyle magazines have always been a convenient means of propagating the newest trends in fashion among the broad community of women. Sometimes, however, the sewing patterns even saved lives. In September 1939, shortly before Britain went to war, a group of British women began preparing patterns for various articles for surgical garments. They worked for the Royal School of Needlework in cooperation with St. John's Ambulance Association and the Red Cross. The patterns were to be sent by the Red Cross to centers to be duplicated in large numbers.

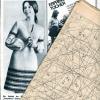

With the division of Europe after 1945, paper patterns continued to play an important role in life. New women's magazines, such as those from Leipzig's Verlag für die Frau in the GDR offered new clothes and also showed women how to keep up with Soviet fashion. At the same time, Burda patterns (then from West Germany) from women's magazines were highly sought after in East Germany and were often smuggled over the border, to allow East German women to keep up with fashions in the West.

Previous Story

Next Story

Previous Story

Next Story

How to cite this page

Slawomir Lotysz, 'One Europe, many patterns', Inventing Europe, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/story/one-europe-many-patterns

Sources

- Stitziel, Judd. Fashioning Socialism: Clothing, Politics and Consumer Culture in East Germany. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2005.

- Kent, Jacqueline, C. Business Builders in Fashion. Minneapolis: Oliver Press, 2003.