Imperial and national canals

The turn of the nineteenth century saw a rise in so-called 'economic nationalism.'

Multinational Empires like Austria-Hungary, nations like France, and even non-sovereign nations like the Czech Kingdom tried to develop infrastructural networks on their territories to increase activity within them. While each country or empire focused on connecting parts of its own territory with uniform technical standards and rules, rivers and navigable waterways already extended past national boundaries.

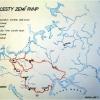

In 1901, the Austrian Parliament sanctioned the Imperial Waterway Act, which envisioned the construction of the unified waterway network on the territory of the empire, with the Danube as its core. Even the most distant parts of the monarchy, such as Galicia, should connect to the Danube via the Dniester and Vistula rivers.

Prussia issued a similar law in 1905. The natural intersection of both schemes, the upper stretch of the River Oder, was completely left out of the Austrian scheme and the Prussians intentionally limited the navigability of the river in their plans. Nonetheless, this meant a new degree of standardization across wide large amounts of space, even if still within national boundaries.

Such standardization was further pursued by the new nation states that appeared after the First World War. In 1921, the German state acquired the jurisdiction over waterways from their federal states and developed a new waterway program. Similar events took place in Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Poland.

At the same time, the international jurisdiction of the Rhine, Danube, Oder, and Elbe guaranteed a certain level of transnational standardization, at least on the larger rivers.

Previous Story

Next Story

Previous Story

Next Story

How to cite this page

Jiří Janáč, 'Imperial and national canals', Inventing Europe, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/story/imperial-and-national-canals

Sources

- Jiří Janáč, European Coasts of Bohemia. Negotiating the Danube-Oder-Elbe Canal in a Troubled Twentieth Century. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.