How Swiss is it?

When construction on the Gotthard tunnel began in 1872, large-scale tunneling was both a booming enterprise and a relatively new technological challenge.

For the francophone Swiss engineer Louis Favre (1826–1879) who won a bid from the Gotthard Rail Company to manage the tunnel construction, the chosen methods had a personal stake as well. He was paid by the linear meter of tunnel, with penalties for every day late and a bonus for every day early. Favre adopted what was known as the Belgian method of tunneling, which involved digging a smaller shaft at what would eventually be the top of the tunnel, and then clearing around it.

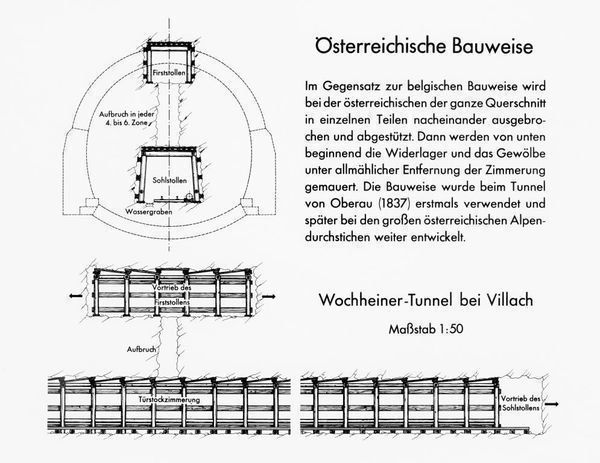

He was aided by a number of new innovations, such as dynamite (patented in 1867) and pneumatic drills that had been pioneered on the Mont-Cenis tunnel. After inspecting the work, the leading Austrian tunnel engineer, Franz Ržiha, criticized Favre's choices, which he saw as both inefficient and less sound than the Austrian method. Favre's adaptions of the Belgian model partly involved the initial tunnel going far ahead, which meant that there was a lot of debris, lack of ventilation, and very high temperatures due to the drilling equipment.

Ržiha's criticisms caused problems for Favre, especially as the project went over time. However, the methods chosen especially had consequences for the mostly Italian workers who had come to build the tunnel. Nearly two hundred of them died, and many more were crippled or made ill.

Favre did not survive the construction either, suffering a heart attack during an inspection of the tunnel in 1879.

Previous Story

Next Story

Previous Story

Next Story

How to cite this page

Alexander Badenoch, 'How Swiss is it?', Inventing Europe, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/story/how-swiss-is-it

Sources

- Schueler, Judith. Materialising Identity: The Co-Construction of the Gotthard Railway and Swiss National Identity. Amsterdam: Aksant, 2008