Expertise and Politics

With the rise of totalitarian regimes following the First World War, the relationship between experts and politics became increasingly strained.

Striving after a say in politics forced experts to question their political position. With hindsight, the 1933 CIAM congress is symbolic, as it was the year the Nazis took over power in Germany.

The CIAM undoubtedly had leftist leanings; nonetheless, only a few of its members had qualms with authoritarian politics. German architects preferred to stay at home, and not to provoke the Nazis. Others, like Le Corbusier, believed that authoritarian regimes made it much easier to realize grandiose schemes, such as completely new cities.

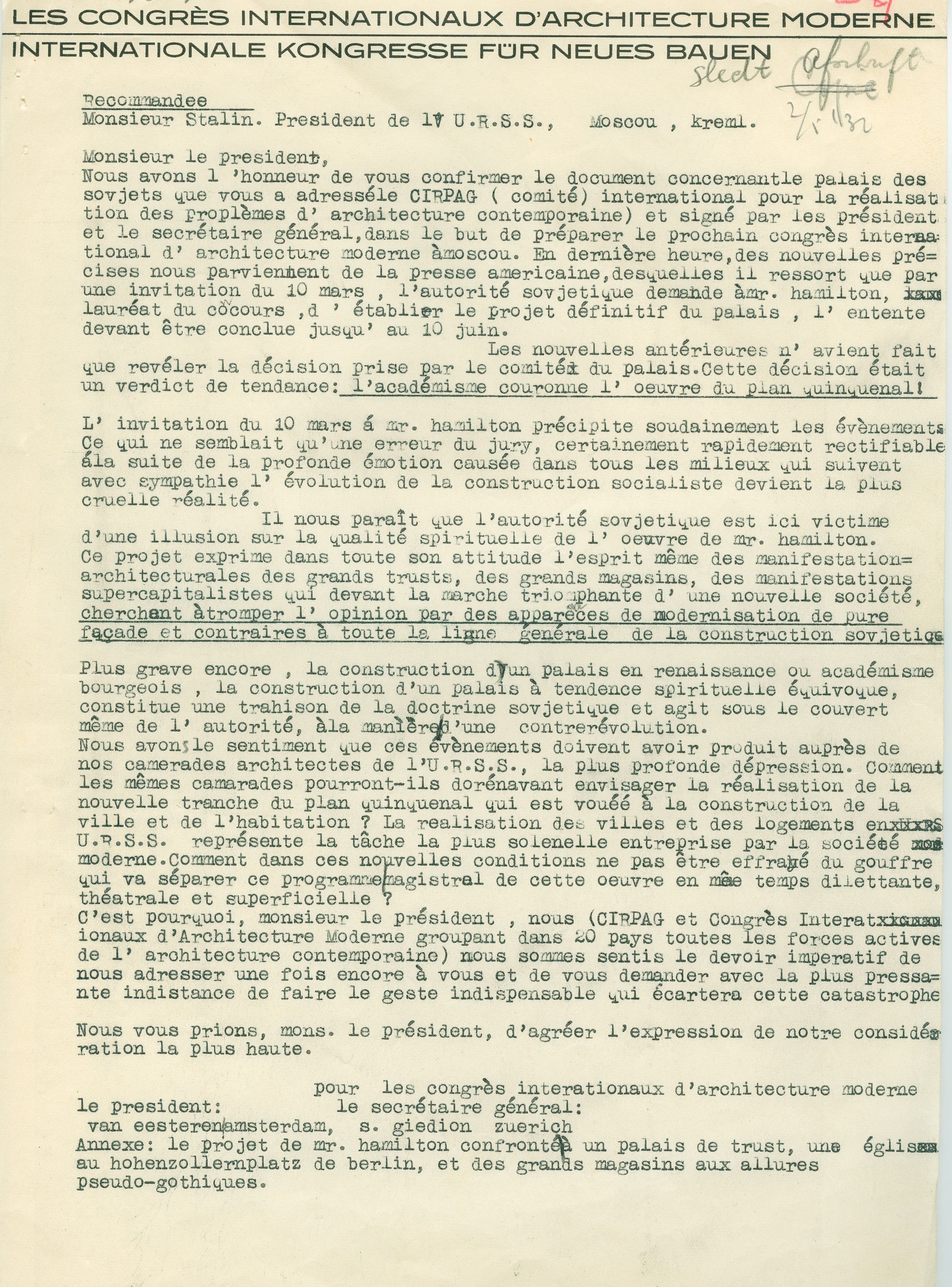

Not by chance, CIAM had originally planned to stage its 1933 congress in Moscow. Due to Stalin’s rather traditional approach to architecture, this never materialized; still, to many architects in the early 1930s, the Soviet Union seemed a place full of hope and glory. Western architects, many of whom had been driven out of work by the world economic crisis, had played a key role in erecting completely new cities in the Soviet Union, such as the widely noticed Magnitogorsk.

Only slowly did these architects realize that rather than dictate policy they would have to closely follow the regimes’ agenda, whether of Joseph Stalin or Adolf Hitler.

Previous Story

Next Story

Previous Story

Next Story

How to cite this page

Martin Kohlrausch, 'Expertise and Politics', Inventing Europe, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/knowledge/expertise-and-politics

Sources

Martin Kohlrausch and Helmuth Trischler, Building Europe on Expertise. Innovators, Organizers, Networkers, London: Palgrave, 2014.

Thomas Flierl, Evgenija Konyseva (ed.), Linkes Ufer, rechtes Ufer: Ernst May und die Planungsgeschichte von Magnitogorsk (1930 - 1933), Berlin: Theater der Welt, 201Nicholas Fox 4.

Nicholas Fox Weber, Le Corbusier: A Life, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008,